The repo markets are fueling the fires again.

Repurchase agreements ("repos") are the sale of securities combined with an agreement for the seller to buy back the securities at a later date, or a cash financing transaction combined with a forward contract. The duration of the agreement can be overnight, term or open. They are heavily used by investment firms to obtain short-term financing that can be rolled over; common financing aims are for longer-maturity, higher-yielding securities to juice the yield spread. Collateral for repo trades include sovereign debt (e.g., Treasuries), agency debt (e.g., Fannie/Freddie or GSE debt), or mortgage-backed securities (MBS). The Federal Reserve also uses repos to inject or withdraw money into/from bank reserves and the money supply, with Treasuries serving as usual collateral.

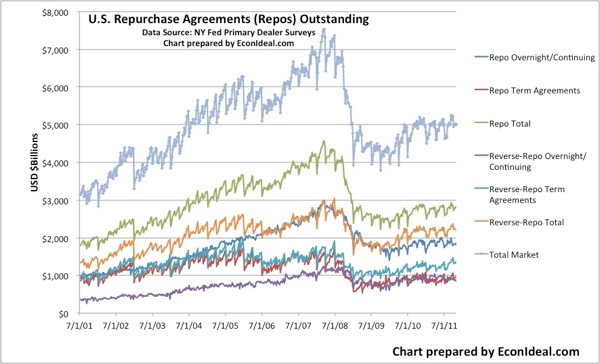

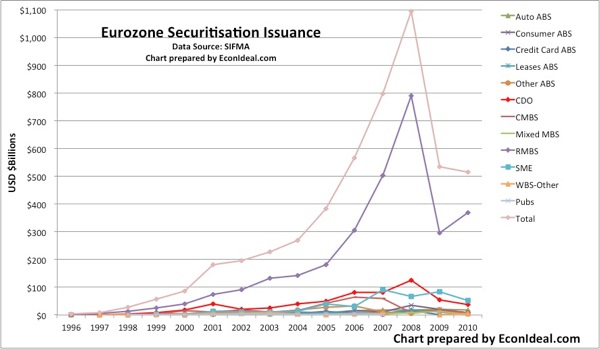

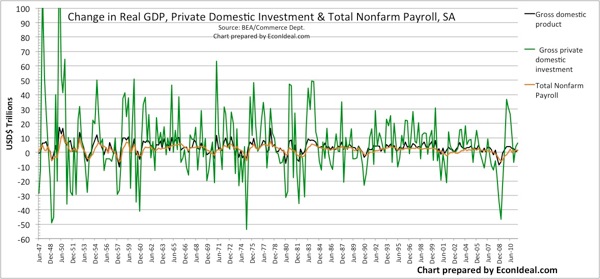

As the curves above show, the repo market size just among U.S. Primary Dealers had grown geometrically in the last decade, until choking following the 2007-8 credit markets seizure. It is worthwhile to note that the growth and decline of these markets correlates with the growth and decline of collateralized debt obligation (CDO) issuance, the same asset and mortgage-backed derivative security that provided a significant contribution to the counterparty risks leading to the credit markets seizure. CDOs were a structured hodgepodge of good and bad mortgage and asset-backed debt, and given a AAA rating from credit rating agencies, making them eligible as collateral for repo transactions, and attractive for their yield. When default rates picked up in 2006-7, the values of CDOs plummeted, and triggered a margin call nightmare that eventually doomed both Bear Stearns and Lehman. The fallout also affected AIG, who sold cheap CDO insurance in the form of credit default swaps (CDS) to CDO buyers, without recognizing the risks should those CDOs implode. The repo markets made most of this "Ponzi finance" of CDOs possible.

It may not be a surprise then that the recent failure of yet another large brokerage firm and primary dealer (MF Global) involved a sizable ($7.6B in March 2011) repo trade with European sovereign debt as collateral. Though MF Global structured the trade such that the maturity of the repo equaled the duration of the European bonds pledged as collateral, thereby seemingly reducing its duration mismatch risk, the firm off-loaded the collateral from its balance sheet as part of the accounting for the repo sale, and in doing so summarily avoided capital cushions to cover shortfalls should that debt lose value until maturity. As the Euro debt crisis heated up this fall, MF Global started getting a barrage of margin calls, then credit downgrades, and then more margin calls. It failed to survive this liquidity thrashing, seeking bankruptcy protection on Halloween. Lehman succumbed to similar fate, and has been accused of employing repo transactions as accounting maneuvers to manipulate its financial reports and leverage, using the funds from repo sales to temporarily pay down debt before repurchasing the collateral ("Repo 105").

To be sure, many repo transactions are used responsibly and legitimately, just as firms responsibly and legitimately use interest rate swaps to hedge interest rate risk. The problem arises when the underlying collateral of the repo trade sharply loses value, and the seller counterparty doesn't have enough capital to survive margin calls and credit downgrades.

The financial instability caused by the exploitation of the repo markets to finance the debt market growth cannot be overlooked, though regulators (Federal Reserve, SEC, et al.) have consistently ignored this major weak point. The worst manifestation of this systemic problem is when such debt market growth leads to "Ponzi finance," a term coined by Hyman Minsky in his classification of financial instability. It is so defined: "expected income flows will not even cover interest cost, so the firm must borrow more or sell off assets simply to service its debt. The hope is that either the market value of assets or income will rise enough to pay off interest and principal." This is precisely what occurred to mortgage and asset-backed debt during the housing boom-turned-bust, as subprime lenders accelerated their loans to unworthy borrowers and sold such bad debt en masse to MBS and CDO packagers/issuers. Those CDOs turned out to contain enough bad debt to invalidate their AAA rating — a rating issued on the faulty basis that default risks were spread out when super-packaged with "good" debt into a structured CDO.

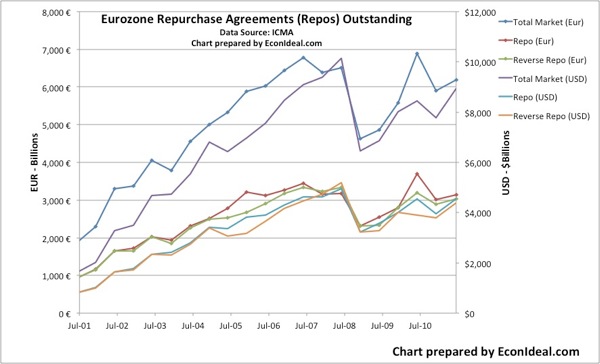

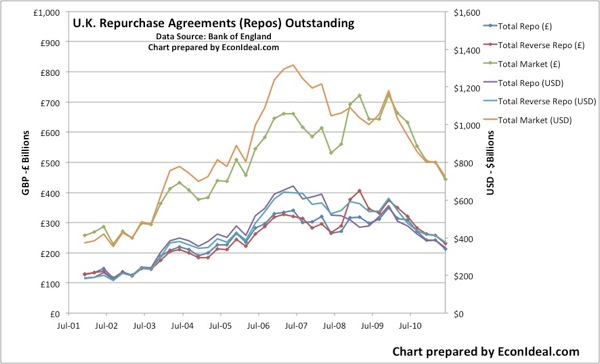

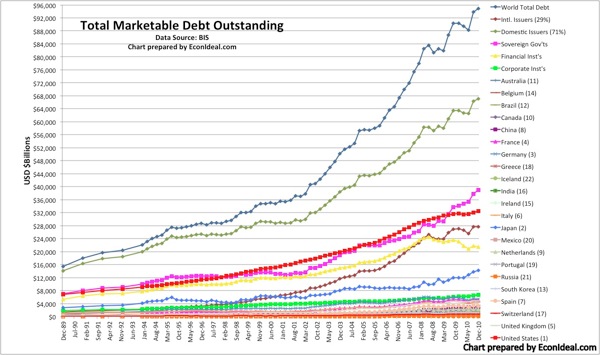

Banks and investment houses still rely too much on repo lines to fund their spread bets (i.e., a lousy business model that just keeps on kicking despite the "systemic risk" and Ponzi finance potential). When the underlying collateral starts to smell, the markets start to seize, and central bank swap lines start to swing. The Eurozone repo market in particular as reported by ICMA declined less than the U.S. repo market and remained elevated after 2008 - and sovereign government and RMBS issuances in Europe increased (see above curves). As already discussed, the growth in the U.S. repo market before 2008 was correlated to the increase in CDO and MBS/ABS issuances, many loaded with subprime "II" junk. Meanwhile global debt outstanding keeps increasing at a record pace.

The opacity of the repo financing markets is an issue that regulators and industry both have failed to address. In particular, the Federal Reserve (specifically the NY Fed) has failed to provide adequate transparency to the U.S. markets, even though it is increasingly charged with regulatory powers that would cover these markets. The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision recently provided a case to strengthen repo clearing and a liquidity/capital framework but certain elements in the system (namely large dealers who want to maintain market share and certain capital terms to draw business) are bucking any changes or improvements that would seek to avoid market seizures and instabilities. Jamie Dimon's rant over the Basel solution is such an example, and JP Morgan has among the largest U.S. market share of the tri-party repo market. Granted, the Basel solution may not be the panacea, but a sensible capital and margin framework and a push to standardized clearing would go a long way, as would market transparency. JPM's role in the MF Global failure ought to be reviewed, no doubt. Let's not forget that JPM was also the repo banker of Lehman and Bear.

The derivatives markets also have suffered from opacity, but in recent years coverage has dramatically improved of both cleared and over-the-counter (OTC) derivative statistics, thanks to the Bank of International Settlements (BIS), DTCC, Tri-Optima, SIFMA, ISDA and other organizations and industry warehouses. In the case of repos, no organization tracks this market with the same level of detail; even accurate market size is not available from existing data [1]. DTCC has started to track a proprietary metric that measures the weighted average interest rate paid each day on General Collateral Finance (GCF) Repos based on U.S. government securities HERE, but not based on other collateral such as EU sovereigns, which has caused much recent consternation and contributed to the failure of MF Global.

Regulators and regulations were not the answer to the repo financing/debt market growth financial instability weak point. Regulators missed Lehman and they missed MF Global. Time after time, financial participants look to arbitrage (avoid) regulatory requirements through creative use of financial products and accounting, and they will continue to do so as avenues are closed, and others opened through "financial innovation" (and sheer desperation for yield and return). I submit that there are three solutions to mitigate this:

- For industry and regulators to provide as much transparency of the repo, debt and derivatives markets as possible, so market participants can gauge exuberant growth and start to correct it through markets before unstable levels are reached;

- Letting firms that abuse financing lines to juice yields or manipulate leverage and capital ratios FAIL, even if they are listed as "systemically important" or "too big to fail" — this will reduce moral hazard and force firms to consider consequences should they ignore prudent risk management or engage in fraudulent accounting;

- Remove the Fed's mandate to control and fix interest rates, which in itself is a source of financial instability, as it leads to excessive endogenous money creation and speculation [2] — the thriving repo markets are but one symptom of this endogenous money activity.

[1] Sizing the vast repo markets is a challenge. The first step is to recognize who participates in these markets and what type of repo agreement those participants enter into. The participants include Fed-approved Primary Dealers (MF Global was one), the Fed itself, and non-Primary Dealers (bank holding companies, insurance companies, etc.). Agreements fall into two general categories: tri-party and bilateral. Tri-party agreements are mediated by a custodian bank or international clearing organization, which act as agents. In the U.S., JPM and Bank of NY Mellon are the major tri-party agents. Bilateral agreements are direct between the repo buyer and seller. The NY Fed provides data on repos between Primary Dealers, which includes its own repo activity HERE, the same as the data plotted at the top. The Fed's publicly available repo activity is broken out in the Fed's H.4.1 statistical release on factors affecting reserve balances, and is a fraction of the reported Primary Dealer activity. The M3 money supply metric, which the Fed used to publish but has discontinued, included its repo activity as well as interbank repo activity. The NY Fed has started to track tri-party repo activity HERE; this data includes both Primary Dealer and non-Primary Dealer participants. When I asked the NY Fed whether their tri-party data could be broken out into PD and non-PD buckets, they told me that this granularity was not available. I also asked the NY Fed for any data they had on repos between non-PD participants, most specifically bank holding companies. They told me that an aggregate was not publicly available through them, and indicated that they do not track such data. Instead they sent me a link to a website they maintain that contains thousands of quarterly reports on bank holding companies HERE, the National Information Center (NIC). When I asked the help desk at the NIC to advise on how to access aggregate data through this site, they responded that the NIC public website did not provide this service and advised me to "check with the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) at http://www.state.gov/m/a/ips/." WOW. If our U.S. regulators are this lousy about tracking and releasing aggregate data, they are indeed impotent to prevent any financial instability! The reader may note that a true market size would include Primary Dealer and non-Primary Dealer, for both tri-party and bilateral agreements. A 2008 BIS report "Development in Repo Markets During Financial Turmoil" does publish data it was able to obtain on repo activity among some 1000 bank holding companies, and that market size is nearly 30% of the huge U.S. Primary Dealer repo market. Eurozone (non-UK) repo markets are tracked by ICMA HERE, and the Bank of England tracks UK repo markets HERE. To the regulators and industry: market participants and researchers are still waiting for a clean transparent total size of the repo markets. A breakdown of collateral, rates and maturities would also be (obviously) useful to track.

[2] See "Federal Reserve Capital Management," which includes a primer on endogenous money.