Do money market funds (MMFs) pose a systemic risk, and if so, to what extent?

This question is still being asked, with continued calls for federal oversight and involvement in "reshaping" the market.

The problem I see is not in asking the tough questions and discussing solutions to preventing market shocks that would destabilize money funds, but in perpetuating myths/misinformation, proposing potentially damaging solutions, and expecting a federal backstop that can increase moral hazard and risk, not decrease it.

[AUTHOR'S NOTE, Jan. 2013: Since the original writing of this piece in May 2012, no major changes to money funds have been made. Individuals at the SEC had been able to provide rationale against the move to require all money funds to carry a floating NAV, a move that I have argued would have created a mass exodus from these funds, and a destabilization of this class of investment. In essence, money funds carrying a requisite floating NAV would become a short-term bond fund, with the possibility of taxable capital gains, as well as principal loss. For paltry yields, investors would see little value in such funds as a place to park cash, with such consequences from fluctuations. They will pull their money out and store it elsewhere. The value in money funds is stability of principal, and as a place to park cash to be deployed in the future toward other investments. Since the November election, the SEC has changed its tune, suggesting that it will support a forced floating NAV, and other investor unfriendly measures. Both the Treasury and the Federal Reserve have been active in supporting these same punative changes. Let me posit that with some $3T+ in assets in money funds, and a waning velocity of money (VoM), the Fed may see this as a measure to compel or coerce investors toward riskier assets, away from money funds, and in turn a chance to provide a stimulus to the VoM. If this is the motivation, it is misguided, and as I point out, potentially destabilizing, causing unintended consequences. When will the Fed, Treasury and SEC figure out that controlling investors and their money is counterproductive? Let the markets (money funds and their customers) decide. My suggested market-based solutions at the bottom of the original article still stand.]

MMFs, also known as money market mutual funds, or MMMFs, are a mutual fund collection of short-term debt instruments that generally mature in 13 months or less, and carry no FDIC insurance; in contrast, money market banking deposit accounts are covered by FDIC insurance but are considerably limited in coverage. The SEC generally requires a 60-day dollar-weighted average maturity of debt instruments held by MMMFs, along with other amendments it made to Rule 2a-7 in Jan. 2010.

It is useful to look at recent trends in MMFs to gauge scale and scope. The Investment Company Institute (ICI) tracks MMMF size, in terms of assets vs. class. Since Jan. 2008, total net assets of all MMMFs tracked went from ~$3.2T to a peak of ~$3.9T in Jan. 2009, remained plateaued around that level until Mar. 2009, and then steadily decreased to a recent low of ~$2.57T (May 2012). This may be correlated with investors fleeing money mutual funds for riskier but higher yielding assets, such as stocks, which have appreciated substantially as a class since Mar. 2009. Notably, from Oct. 2008 to Jan. 2009, MMMFs gained total net assets at a rapid pace, no doubt correlated with the market selloff of risk assets, but also coincident with the commitment from the Fed to provide a money market investor funding facility (MMIFF), one of many funding facilities seeking to buy distressed assets in exchange for monetary "liquidity."

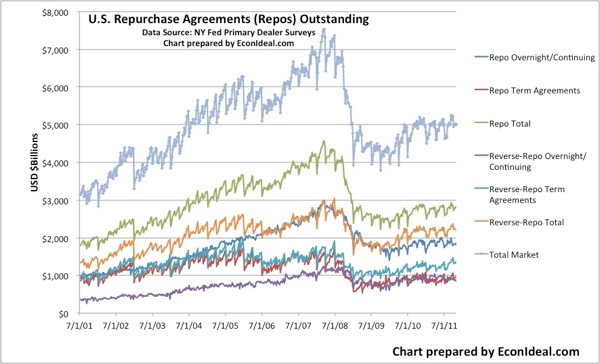

Since providing the MMIFF and other facilities to money funds, the NY Fed has more recently instituted a reverse repo counterparties list, which is loaded with the major MMFs that carry the bulk of money fund assets outstanding. Ostensibly the stated purpose of this action was to "conduct [a] series of small-scale reverse repurchase (repo) transactions using all eligible collateral types" in an effort to "ensure that this tool will be ready to support any reserve draining operations that the Federal Open Market Committee might direct," meaning to remove liquidity. However, it can also be seen as a mobilization of all major parties to provide even more liquidity, should there be future systemic shocks. Those who follow the Fed's regular H.4.1 releases know that this would mean simply shifting the small liabilities in the RRP line to the assets in the RP line. (The RP line and the asset side of the balance sheet spiked in 2008-9 as the Fed provided repo and other facility loans for qualified assets.)

One issue is that MMFs may see these programs and actions by the Fed, which is not an independent entity but a government-sponsored regulator and policy maker, as an implicit backstop, perpetuating the more general moral hazard problem that led to broader market shocks in 2008. Some at the Fed have recently studied risks to MMFs (cf. E. Rosengren, "MMMFs and Financial Stability"), concluding that actions are needed, but again, there remains the matter as to what effect these actions would have, detrimental or positive.

The MMF "shock" in 2008 can be traced to a single bad actor, the Reserve Fund, breaking the buck as a result of holding toxic Lehman commercial paper, losing investor money in the process as a result of not having a fund "sponsor" to shore up losses. Arguably, this case was an aberration and distortion, and has been overhyped as a rampant problem, when in fact many MMFs did not have anywhere near that type of risky exposure on the books. True, Rosengren cites other cases in his study, and in those other cases the funds in question had a backstop from corporate sponsors to stem losses.

Going forward, the systemic risk issue exists from MMFs taking on excessive credit risks that basically result from "duration mismatch," or the process of borrowing ultra short to finance long (the juiced yields strategy). No doubt this activity breaches risk management standards, and any MMF employing this strategy to entice investors is placing those investors at risk and should be avoided. The question is how likely is this happening now, or to happen in the future on a level that would pose a great systemic risk?

A cursory look at the current holdings of a few major MMMFs show the following [1]:

Vanguard Prime MMF: CDs (3.6%), Commercial Paper (10.7%), Repo (0.4%), U.S. GSE/Agency Debt (24.7%), U.S. Treasury Debt (30.3%), Yankee/Foreign (25.5%), Other/Muni (4.8%); Ave. Maturity: 60 days, Yield (tty): 0.04%, Mgmt Fee: 0.20%, Min Inv: $3K

Fidelity Institutional Prime MMF: CDs (34.5%), Commercial Paper (12.1%), GSE/Agency Repo (21.3%), Other Repo (5.9%), U.S. GSE/Agency Debt (2.7%), U.S. Treasury Debt (16.9%), Other/Muni (6.6%); Ave. Maturity: 43 days, Yield (tty): 0.10% (0.13% 7-day), Mgmt Fee: 0.21%, Min Inv: $1M

Blackrock TempFund Institutional MMF: CDs (39.2%), Commercial Paper (17.3%), GSE/Agency Repo (6.5%), Treasury Repo (1.4%), Other Repo (3.4%), U.S. GSE/Agency Debt (10.9%), U.S. Treasury Debt (9.8%), Time Deposits (4.7%), Other/Muni (6.8%); Ave. Maturity: 51 days, Yield (tty): 0.11% (0.12% 30-day), Mgmt Fee: 0.18%, Min Inv: $3M

Federated Prime Rate USD Liq MMF: CDs (13.3%), Commercial Paper (33.7%), Asset-Backed Securities (0.9%), Bank Notes (4%), Corporate Bonds (0.6%), Bank Repo (23%), Variable Notes (23.1%), U.S. GSE/Agency Debt (0.9%), U.S. Treasury Debt (1%); Ave. Maturity: 31 days, Yield (tty): 0.13% (0.16% 7-day), Mgmt Fee: 0.20%, Min Inv: $25K

This sample includes a major retail fund, two institutional funds, and as a contrast, a large off-shore MMF. (For the U.S. MMF market, according to ICI the split between retail/institutional funds in terms of asset size is roughly 35/65%; Prime funds make up about 55%, with tax-exempt/muni and gov't-only funds split at 11/34%.)

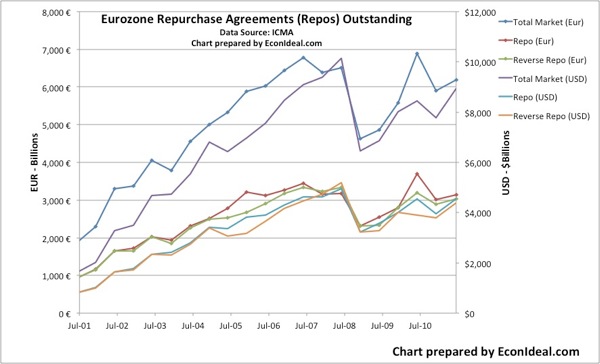

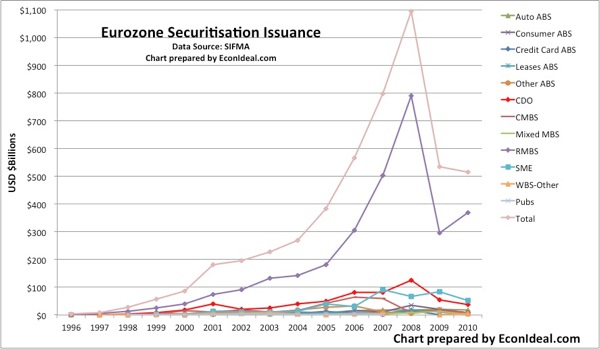

Clearly the portfolio mix of short-term yielding assets of the U.S. MMFs in this sample is quite variable, but this shows that there has been a trend shift from funds holding a greater percentage of commercial paper (particularly asset backed), asset-backed securities and muni debt (variable notes) a few years ago toward Treasury and GSE/Agency debt. MMFs also shifted to holding European debt (via repos and other holdings), but this activity peaked in mid-2011 and declined substantially by Dec. 2011 due to the Euro-debt crisis heat (see Figs. 5/6 in Rosengren's study). Shifting from these higher risk assets has meant a considerable decrease in yield, which in most cases is now a fraction of the management fee of the fund (!). The off-shore fund, from Federated, does have a significant repo exposure, in particular agreements with three major European banks. Fidelity has a significant repo exposure, but backed by GSE/Agency debt.

Let me ask a rhetorical counter-question: with the Fed forcing money yields (short-term interest rates) so low for an "extended" period, are they not squeezing/forcing investors to seek riskier assets, and might that bias lead to a potentially dangerous systemic outcome itself?

Perhaps we need a reminder as to why investors seek MMF positions: nominally it is for capital preservation, a place to park cash safely, but also to collect "low-risk" yield. True, the yield ought to be matched to the risk, and the lower the risk, the lower the yield. With negative real yields, investors are choosing to pull money out of MMMFs, as the data trends show over the last three years. However, there are still investors that demand a place to park cash "safely" and expect capital preservation. That is why I think that the call from numerous sides for the elimination of the stable net asset value (NAV) of MMFs would be a major discouragement to investors who seek stable value capital preservation - if the stable NAV is replaced by a floating NAV investors might choose to pull all their money out of such funds. One could even argue that such an exodus would itself pose systemic risk problems.

So here's a real solution.

- Let the market determine demand and provide a way to supply that demand. If MMF investors want stable NAV, let the industry settle on a way to continue to provide it with clear disclosure of risks. If investors will tolerate a floating NAV in exchange for greater yield/risk, provide that option. Let the market provide the product options/choice - it ought not be dictated by the SEC or the Fed.

- An industry-led voluntary "liquidity fund" or capital buffer fund is a sound way to address MMF "systemic risk" issues that might occur. This would eat into any yield, but it might be worth it to investors looking for stable values and capital preservation, and a way to "insure" it. The business case for this option should be pursued and presented to investors. This solution trumps a TBTF backstop from the Fed and/or Treasury, which costs everyone in the end and leads to greater moral hazard, not less.

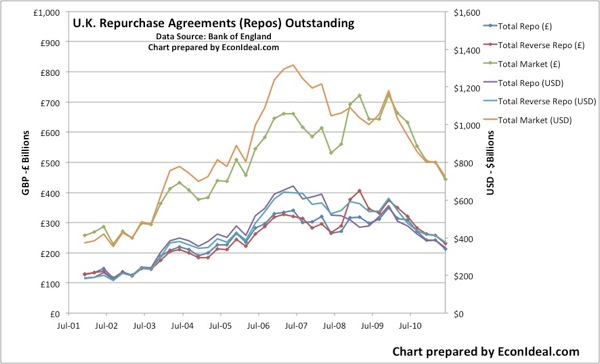

I will end this piece by stating that the repo markets pose more of a systemic risk/financial instability concern than MMFs. (See my earlier piece on this HERE.) Though MMF holdings (as least the sample of major USD-based funds above) show a diversity of short-term assets, with repo generally in the minority, Fidelity still holds a substantial set of agreements against GSE/Agency debt, and off-shore funds continue to lend to major European repo counterparties. Counterparty risk, as well as the credit and interest rate risks of the underlying repo collateral assets, are always material. Primary dealers are addicted to the repo markets and it is clear that addiction isn't going away, given the dynamics put in motion by the system (the Fed and other central banks) to keep government borrowing costs low, while providing a steady liquidity stream to players that want to profit on the spreads. We all know what happened to MF Global when it over-leveraged on European sovereigns repo debt. The basis for that over-leverage was that the underlying debt would recover, and it didn't, at least not fast enough. Interest rate risk (and default risk) on sovereign and GSE/Agency debt, including U.S. Treasury and GSE/Agency debt, is not insignificant going forward, and even money funds need to be aware of this.

[1] I obtained MMF portfolio holdings from individual fund sponsor websites. A good place to view rankings and recent liquid yields of MMFs is iMoneyNet.com.