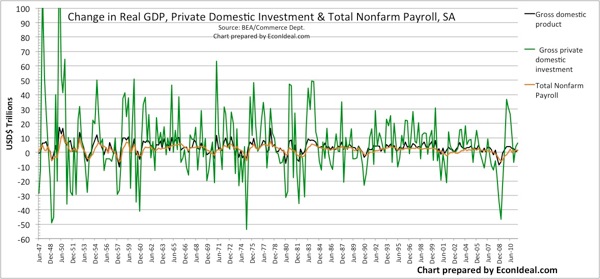

Those connected with econometric data are all too aware of the first chart. Less attention and focus goes to the components of real gross domestic product (GDP) and their trends, particularly private domestic investment (PDI), which historically leads to real economic growth and job creation. The correlation for this comes from looking at the change in real GDP, which responds to changes in PDI [1].

The historical trend for PDI has been relatively weak and muted, despite its multiplier effects on real growth and jobs. The period of the greatest compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) in PDI since 1947 occurred from June 1992 to June 2000 (9.3%; $985B to $2.01T). At the same time, growth in government expenditures was relatively flat (1.4%). Speaking to our trade deficit crisis, net exports (exports-imports) increased negatively at a CAGR of -36.6% (-$36B to -$439B). Personal consumption grew steadily (4.2%) with real GDP growth (4.0%), confirming the moniker "consumer-driven economy."

Since the "prolific" 1992-2000 period, the trend has reversed on PDI. From June 2000 to June 2011, PDI shrank with a negative CAGR of -1.1%, and the current value is stuck at around 2001 levels. While it is true that real GDP and the components kept growing until the 2006-7 pop in the mortgage bubble, PDI has not robustly recovered since the 2008 plunge. A large contributor came from the plunge in residential fixed investment, which we may classify as synonymous with personal consumption, given the hefty progression of homebuyers and speculators that took on mortgage debt and refinancings to finance further consumption. But what about nonresidential fixed investment? Why is it not showing healthy robust growth? Embarrassingly, government expenditures have outpaced at a 1.6% CAGR, and real GDP and employment remain flat to down.

What are the plausible causes of the dearth in PDI, specifically the contributions coming from nonresidential fixed investment? I provide a list below, which is by no means complete:

- Government regulations are too many, too costly, without justifiable cost benefits

- EPA, Labor Dept (employment regulations), Sarbanes-Oxley, Dodd-Frank, ...

- Monetary and tax policies support/induce consumption/speculation, not investment (nonresidential PDI) that leads to solid job creation

- Zero interest rate policy (ZIRP) and quantitative easing (QE) induce speculation and malinvestment, distorting risk-reward

- Significant overseas profits remain unavailable for domestic investment due to punitive corporate tax policy

- Tax code growth has coincided with providing vote-buying tax subsides linked to consumption; increasing complexity and uncertainty in the code represent a fundamental drag on business growth

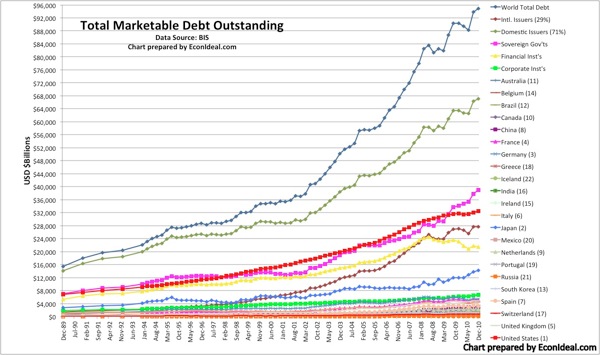

- Government expenditures crowd out PDI, and may have as damaging an effect in the future as mortgage debt consumption did in the recent past

- Government stimuli (including subsides), social "entitlements" and welfare ($9T+ marketable Treasury debt, $5T+ non-marketable debt, $100T+ off-balance-sheet liabilities)

- False safety in Treasuries and the sovereign credit rating

The bottom line is that unless we address the inhibitors to PDI, specifically nonresidential fixed investment, we risk stagnant growth (or worse) for the foreseeable future.

[1] The charts showing the correlated trend between real GDP and PDI, and total non-farm payroll and real GDP, are shown below: